We are proud to introduce the first installment of our series on “Slargon” with John Cook, a PhD Candidate and climate change researcher with the University of Queensland.

Sometimes it takes a conversation over dinner to see the bigger picture, and that’s exactly what happened to John Cook. Over dinner conversations about climate change with his in-laws a few years ago, John began to notice how confusing climate change science sounded and how “sticky”, or how easily-repeatable, myths could be perpetuated in climate talks. He knew he had to do something to fight back against bad information sticking.

Part of the problem to John was the way information was delivered to people. Scientists communicate climate science in a complex way, using technical jargon and slang that would confuse people who were not specialists in the field. How scientists frame debates and how journalists and communicators frame debates are very different, and John understood the need to bring both languages to the same level. In response, he has devoted the last five years to debunking climate change myths and smear campaigns. He started a website called Skeptical Science, which takes a myth-busting approach at explaining misinformation surrounding climate change debates. John is also pursuing a PhD at University of Queensland studying the psychology of climate change, and is researching ways communicators use slargon to spread confusion about climate change science. We are happy to share his ideas about the use of language in climate communications.

___________

John Cook presenting research on man-made global warming in scientific literature to Professor Naomi Oreskes, author of Merchants of Doubt.

1. Tell us a little bit about your background.

I started out studying a physics degree at the University of Queensland. After finishing my degree, I worked in a range of areas – database programming, illustration, web design, cartooning and screenwriting. All of these experiences and acquired skill sets ended up playing a part in my current climate communication work.

2. Given your background in physics, what got you interested in the issues of climate change denial and misinformation?

I first became interested in climate change getting into “vigorous discussions” about climate science with family members (predominantly on the in-laws side). In researching the matter, I discovered that the arguments against climate change had very little scientific basis. So in preparation for the next family get-together, I started a database of various climate myths and what the peer-reviewed science said about each myth (you can’t leave anything to chance with tussling with the in-laws). That database eventually formed the basis for the Skeptical Science website.

3. How has your work with your website and your Massive Online Open Course (MOOC) development work changed or reinforced your perspectives on climate change communication?

In 2010, I received a life changing email from a psychology professor that included some psychological research into debunking. The research found that if your debunking wasn’t structured properly, you ran the risk of actually reinforcing the myth you were trying to debunk. This startled me to say the least and drove home the crucial importance of social science research into science communication. Since then, I’ve been studying the psychological research into science communication, as well as conducting my own research. Our MOOC, “Making Sense of Climate Science Denial”, is a video summary of my investigation into the psychology of denial – explaining what drives climate science denial and how to respond to it.

4. What role do you think language – specifically, slang and jargon that is often used in the media – plays in climate change communication?

It took me a number of years before I realized that science communication wasn’t just about understanding and explaining the science. Communicators also need to understand their audience. This means having a grasp of the psychology of how people process information. Framing matters. Words that mean one thing to a scientist can mean an entirely different thing to a non-scientist. So it’s crucial that scientists are conscious of the words that they use, and whether those words hold the same meaning for the audiences they’re talking to.

5. You maintain a website called “Skeptical Science”, which debunks climate change denial arguments in a Snopes-like manner on the Internet. Have you identified a common style of argument from deniers?

There are common styles of arguments that apply not just to climate science denial but any form of science denial. We see it with creationism, anti-vaxxers and the tobacco industry’s denial of the health impacts of smoking. In all movements that deny a scientific consensus, we see five telltale techniques that distinguish denial from genuine scientific skepticism. I use the acronym FLICC to remember them:

- Fake experts: spokespeople who convey the appearance of scientific expertise but have no actual scientific expertise in the topic at hand.

- Logical fallacies: using fallacious arguments such as ad hominem attacks (attacking someone’s character), straw man arguments (arguing against a point someone did not make) and red herrings (presenting irrelevant diversions) to distort or distract from the science.

- Impossible expectations: raising the level of proof to an impossible level, a technique perfected by the tobacco industry decades ago to delay cigarette regulation.

- Cherry picking: rather than taking a holistic view of the full body of evidence, this involves selectively focusing on a small piece of data and ignoring all contrary evidence.

- Conspiracy theories: inevitably the only way to explain why you disagree with a global community of scientists is to resort to conspiracy theories.

6. How do you effectively respond to arguments by people who deny climate change?

There are two important elements to responding to denial. Firstly, if you debunk a myth, you need to replace it with a factual alternative. When you explain that a myth is wrong, you create a gap in a person’s mental model of the world. You need to fill that gap or the myth will come back and continue to influence people. And here’s the kicker – the fact needs to be even more compelling, memorable and “sticky” than the myth you’re displacing. This is the golden rule of debunking: fight sticky myths with stickier facts.

Secondly, you also need to explain the technique that the myth uses to distort the science. If people don’t understand the myth’s fallacy, they have no way of reconciling the fact with the myth. This is why FLICC is so important – it provides a framework for understanding the different techniques of science denial.

7. You also published a report in 2013 that aggregated scientific papers about climate change and found a 97% consensus endorsing the position that humans are causing global warming. Tell us a little bit about this process and your conclusions.

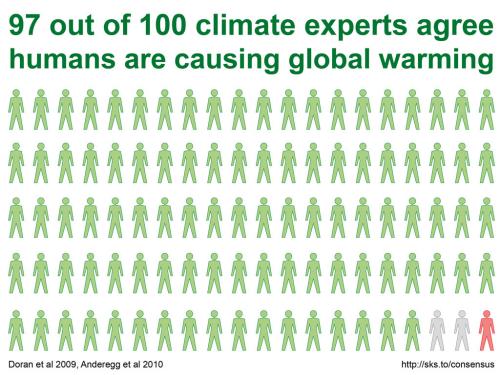

In 2004, Naomi Oreskes published a study analyzing the level of scientific agreement on climate change in published climate papers. She found overwhelming scientific agreement that humans were causing global warming. Nearly a decade later, we thought it was high time to update the analysis – so we repeated (and expanded) her analysis, looking at 21 years of climate papers. We found that among the papers stating a position on human-caused global warming, 97.1% endorsed the consensus. We then invited the scientists who wrote the climate papers to rate their own research. That yielded a 97.2% consensus.

The reason why this research is so important is two-fold. Firstly, the public think there’s a 50:50 debate among climate scientists about whether humans are causing global warming. Secondly, when the public think scientists disagree, they’re less likely to support climate mitigation policies. So closing the “consensus gap” is necessary to remove one of the roadblocks delaying climate action.

8. How did the public receive this study? Was there backlash?

The initial reaction was surprise: “really, the consensus is that high?!” I have to confess, I was surprised at the level of surprise. Ours wasn’t the first study to find 97% scientific consensus on human-caused global warming. Using different methodologies to us, Peter Doran found 97% consensus in 2009 and William Anderegg found 97% consensus in 2010. But casting doubt on the consensus has been a key tactic by those opposing climate action for decades.

The next reaction was attacks on our research from people denying the scientific consensus. Those attacks have continued for over two years, taking the form of blog posts, newspaper op-eds, reports by conservative think-tanks, online videos, cartoons, papers, complaints to my university, Freedom of Information requests for my emails, TV interviews and congressional testimonies. As a scientist researching misinformation and science denial, what interests me is that the attacks on my own research have adopted the five techniques of science denial – an interesting source of data to analyze!

9. What was the strategy behind framing this as “anthropogenic global warming”? Were there alternatives?

Personally, I avoid using the term anthropogenic when talking to the general public, which is why I generally opt for “human-caused global warming”. Another alternative is “man-made global warming”.

10. What do you think is the most effective way to deliver the scientific information about climate change?

The key to communicating climate science, and in fact the key to communicating *anything*, is to make your information “sticky”. A book that I’ve found very helpful is Made to Stick, by Chip and Dan Heath. They use the acronym (I do love acronyms which are very sticky) SUCCES to summarize the traits of sticky ideas:

- Simple

- Unexpected

- Credible

- Concrete

- Emotional

- Story

11. Do you think we are moving towards a better global understanding of anthropogenic climate change?

From a scientific perspective, climate scientists have a strong understanding of human’s role in global warming. We have observed many human fingerprints in our climate, all pointing to a single, consistent picture. As for global understanding of climate change, perhaps the most important indicator is public momentum towards meaningful climate action. In 2015, this momentum seems to be building as we head towards the December international climate negotiations in Paris. I hold a cautious optimism that we will see the world’s countries take significant steps in the right direction at those negotiations. If we see strong leadership on climate change, we’ll then see significant flow-on effects regarding public views on climate change.

12. You’re currently pursuing your PhD, what is the focus of your latest research?

My PhD research is on the psychology of climate change and science denial. I’m particularly interested in how scientists should respond to misinformation and science denial. This research journey has led me to an intriguing body of psychological research into “inoculation theory”. This research finds counter-intuitively that the way to stop science denial from spreading is by exposing people to a weak form of denial. This has been the approach of our “Making Sense of Climate Science Denial” MOOC.

13. Where do you get your inspiration to study climate change communication?

Ultimately, what drives me is being a parent wanting to hand over a safe world to my daughter. I identified that a key way to achieve the action needed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change is to raise public awareness of the realities of climate change. One of the roadblocks to public support for climate action is misinformation, so I research the most effective ways of reducing the influence of misinformation.

14. Do you have any referrals for more information, or any other ideas you can share?

For a crash course on climate science, the psychology of climate change and the research into debunking misinformation, I recommend our free online course Making Sense of Climate Science Denial.

A shorter introduction the psychology of debunking is available in The Debunking Handbook (which was recently translated into a 10th language).

Recent Comments