Earlier this week we showed you several famous people and asked you what they all have in common. The answer is that all of them are powerful speakers who have managed to make memorable speeches that influenced and inspired people throughout history.

So what makes a great speech memorable? Delivery, humor, emotion, and tone to name a few. What makes a great speech resonate with its audience? Word choice. Choosing the right words can make or break a speech. How the media or your opponent interprets your words can halt progress and change your image in an instant.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivering his first inaugural address.

(Credit: Youtube user Alexander Stern)

A classic example was in 2010 when BP‘s Chairman Carl-Henric Svanberg told reporters in Washington, days after the disastrous oil spill in the Gulf Coast, “I hear comments sometimes that large oil companies are greedy companies or don’t care, but that is not the case with BP. We care about the small people.” The media and many of those affected by the tragedy jumped on the second sentence, labeling him an out-of-touch elitist when it may have just been a slip in translation for the Swedish-born Svanberg. While these gaffes may not have been as noticeable a decade ago, smart phones, the Internet, and social media have helped to catapult them around the world and preserve them in a click of a mouse.

As we start our focus on word choice this month, Collaborative Services spoke with someone who knows the ins and outs of word choice. As a speechwriter Robert Lehrman has chosen the words used by our country’s leaders, corporate top dogs, and celebrities. Most notably Lehrman worked as the White House Chief Speechwriter for Vice President Al Gore from 1993 to 1995. Today, Lehrman is still in the business of choosing the right words but in addition to speeches, they are now often under his name. Lehrman has written several award-winning novels, teaches Speechwriting as an adjunct professor for American University (AU) and other schools, and is author of The Political Speechwriter’s Companion (CQ Press, 2009) in wide use on campuses and by politicians in both parties. He has been featured in the Washington Post, New York Times, Christian Science Monitor, and Politico. In 2010 Lehrman and his colleague, AU Professor Leonard Steinhorn launched the website PunditWire as a place where political speechwriters comment on the news.

Collaborative Services spoke with Lehrman about his role as a speechwriter, author, and professor, how word choice helps persuade an argument and audience, and some of his favorite speeches. We welcome his insights.

– – –

You’ve been a speechwriter for governors, senators, CEOs, and probably most notably, Vice President Al Gore. Can you talk about the role word choice plays in making a persuasive argument? Are there some words you lean on, and others you like to avoid?

It plays a central role — but not just in the way strategists suggest. They often focus on the implication of words.

For example: Frank Luntz, who writes a lot about how choosing the right words matters in persuasion, points to the difference between Colin Powell‘s term for what he recommends nations use in going to war—”decisive force”— and the way reporters describe Powell’s view: “overwhelming force.” There’s definitely a difference and those choices matter.

But what about choosing words people are more likely to understand?

Americans average a 7th grade reading level. When I write for politicians I choose “use” not “utilize,” “now” not “currently,” and dozens of other choices that let more people understand. Do you want to persuade people? Make sure they understand you.

How does word choice differ when you’re writing for a political leader, a business leader, or other speakers?

If the topic is the same — and if the audience is the same — my approach to language doesn’t vary much. I always want to use language people understand, concrete detail, clarity, and some devices people use to make speeches memorable — antithesis, or alliteration, for example.

But there is one big difference between corporate and political speech. In politics it’s common to attack the other side (“Democrats have done nothing!”). Corporate CEOs don’t do that. The Merck CEO won’t say, “Novartis has done nothing.”

In fact, even when they complain about government regulation, which they do often, corporate speakers want to sound more temperate. So those attack words and litanies of complaint pretty much vanish when I do corporate.

Are there any words that have positive or negative connotations that the average person might not think of?

Plenty. One reason? Our biases. Here’s one example. Someone who opposes abortion might think “pro-life” has no negative connotation. Because they believe an embryo is human, “pro-life” seems positive. To someone believing in Roe v. Wade the term might be infuriatingly negative — implying that those who support the right to abortion don’t care about life. The same thing is true — in reverse — about “pro-choice.”

When delivering a speech, which is more important – the writing, or the speaker’s execution?

There’s no one answer to that. When John F. Kennedy gave his 1963 speech suggesting a limit to nuclear testing, the most important thing was what he proposed. He could have mumbled through the speech and still accomplished his goal — reaching out to the Soviets. And actually, he didn’t deliver it very well.

But Martin Luther King Jr.‘s “Dream” speech that same year? He has some powerful material. But it’s hard to imagine the speech succeeding without his resonant voice, enormous variety, effective use of pause and emphasis, and the way he raises his voice from step to step in his closing call to action.

Dr. Martin Luther King delivering his famous “I have a Dream” speech.

(Credit: Hearst Communications Inc./timesunion.com

In addition to speeches, you’re also an award-winning novelist. You’ve written three books for young adults and one for adults. Can you talk about how you alter your word choice depending on whether you’re writing for young readers or more mature adults? How does word choice in novels differ from speeches?

I wrote my first novel, Juggling, as a book about adolescents aimed at adults. Harper & Row published it as a young adult (YA) book. But because I thought of my audience as adults I didn’t think at all about making sentences more accessible. Naturally, that can’t apply to every book for younger readers. You can’t write like Proust and hope to attract 12-year olds. Or at least many of them.

I did think about using shorter sentences, simpler language, and less detail for my two other YA novels — though not as much as you think, and it’s not easy. After all, you can say a lot with words of one syllable, but at some point you rob a passage of richness and nuance. Where is that point? I wrestled with that question, not always to my satisfaction. As for how this differs in speech — see the next question.

As a professor, how do you make your students aware about the importance of word choice?

We have two units in my course specifically about word choice — one on clarity, the other on how to be memorable. I could go into great detail about the things we talk about when it comes to being clear — but they’re not unusual. We work on being less wordy, concrete detail, and simple language.

Memorability? That’s different. We work on something you will see in almost no other kind of writing: repetition. In most writing courses repetition is something to avoid. In speeches, litanies using the same grammatical structure adds power — there’s a reason Martin Luther King Jr. said “I have a dream” about eight times. And there are specific devices that make speeches memorable. I hate to load this down with the technical terms but don’t know another way to quickly give readers things to look up: antithesis, antimetablole, anaphora, epistrophe, chiasmus are some.

Finally, I urge students going into political work to write speeches average people can understand, which means writing at a seventh-grade level. That’s controversial — there’s one academic who argues that this dumbs down rhetoric to the point that Presidents can’t make points with the sophistication that allows them to lead. But a President is often heard by millions of people — even rallies see 30,000 people in the crowd. It’s undemocratic to present ideas in language most voters can’t follow. Even writing at an 11th grade level means half of the average voters won’t understand. In politics, you can’t go to your boss and say, “I have a profound speech for you — but half the audience won’t know what you’re talking about.”

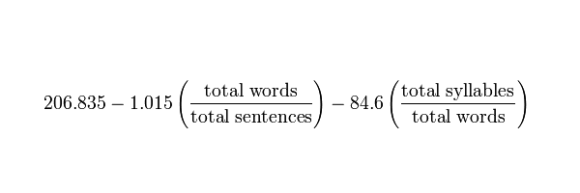

This might be a good place to point out that in Microsoft Word we have an immensely useful tool, often ignored, that helps speechwriters do that. If you go to the “Spelling and Grammar” option, click on “Options”, and find the box under “Grammar” you’ll see the box next to “Readability Statistics.” If you check it and click “OK” each time you finish Spelling and Grammar, a box opens up with all kinds of useful information — average sentence length, percent passive voice, and other things. It tells you what grade level you’ve written at — and how many Americans can “easily understand” what you wrote.

Naturally, they use a formula for this — Google “Flesch-Kincaid” if you want to know more. It’s possible to fool the guide. But on the whole it’s pretty good. I use it for all my speeches and insist students do the same. It amazes them how high their passive voice level is — and how much more energetic their writing gets when they reduce it.

Are there any well-known speeches that you consider a favorite, an inspiration for your own writing, or something you assign all your students to read? What about them makes them so powerful, in your opinion?

It’s rare to find a speech that’s powerful all the way through in politics. When people go to the famous speeches they will see a word or section that’s memorable (“We have nothing to fear but fear itself.”) and be astonished to see how mediocre the rest is. And so, in this list of speeches I love to teach, none are perfect. But there’s usually one section that stands out. And so, in this list, it’s usually one section that stands out.

Ronald Reagan: 40th Anniversary of D-Day: Note the gripping way he uses the story of the invasion to compel us from the first 30 seconds.

Ronald Reagan: Farewell from the Oval Office: Here note the way he humanizes himself in the opening by describing the way things look outside the White House windows — and the windows of his motorcade — as well as the story about the Vietnamese boat people to symbolize his administration.

Barack Obama: 2008 Victory speech: Here’s a stunningly original close, in which Obama uses the story of one 106-year old woman to encapsulate the history of the last century — leading into his “Yes we Can” litany that sweeps the audience along.

Conan O’Brien: Harvard 2000 Class Day speech: Yes, it’s 12 years old — and a testament to whoever wrote this speech with more laughs per page than I have ever seen, and a great example of how effective humor can be in speech.

Comedian and Talk Show host Conan O’Brien made his speech to Harvard’s Class of 200 memorable using humor.

(Credit: Dallas Movie Screenings)

As language changes and evolves, have you noticed speech writing changing in any way? Are there any words you would use now that you would never have used ten or twenty years ago, or vice versa?

As ideas become acceptable there are words you find in your speeches that wouldn’t have been there a decade back — like “same-sex marriage.”

Not all the changes over the last few decades involve word choice, though. Since I started writing speeches I see three changes. First, litanies of repetition — popularized by JFK and King. Second, the use of antithesis, or repetition to show contrast (“Ask not what your country can do for you …”), which also probably came from JFK and which you’ll see as many as 10-15 times in an Obama speech.

The third, using story to move or dramatize. There are no stories in the JFK Inagural address, or in King’s “Dream.” Reagan’s writers used story so effectively it influenced other writers to do the same — I know that influenced me.

– – –

Next time you are tasked with writing remember the goal is to persuade or influence as many people as possible. Know your speaker, their audience, and the opposition if there is one, and evaluate how readable what you wrote is. To learn more about writing and word choice from Robert Lehrman you can purchase his books here.

Liz Faris, Associate

Collaborative Services, Inc.

Recent Comments